From Beyond the Grave

Essay by Ariel Dorfman

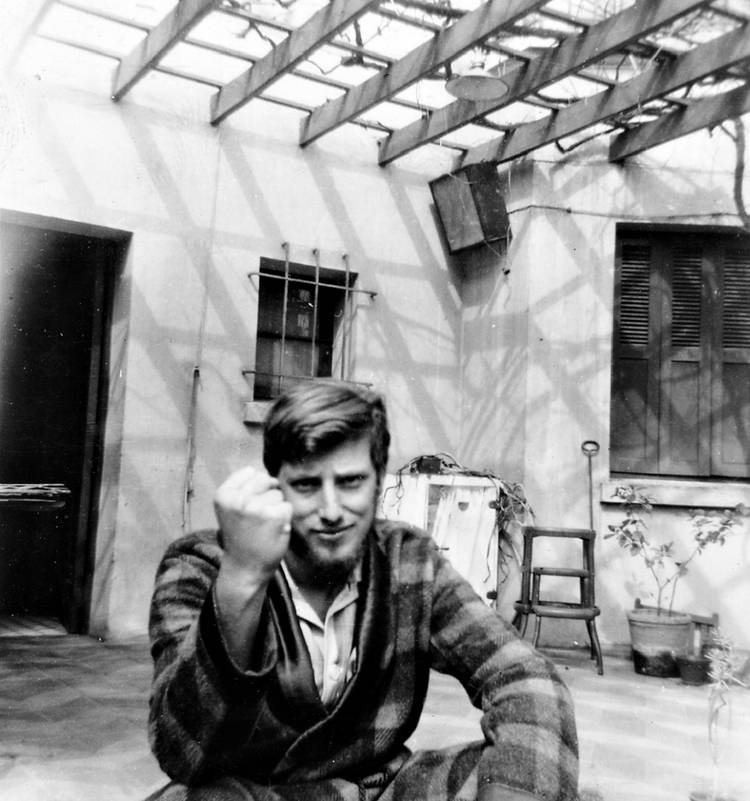

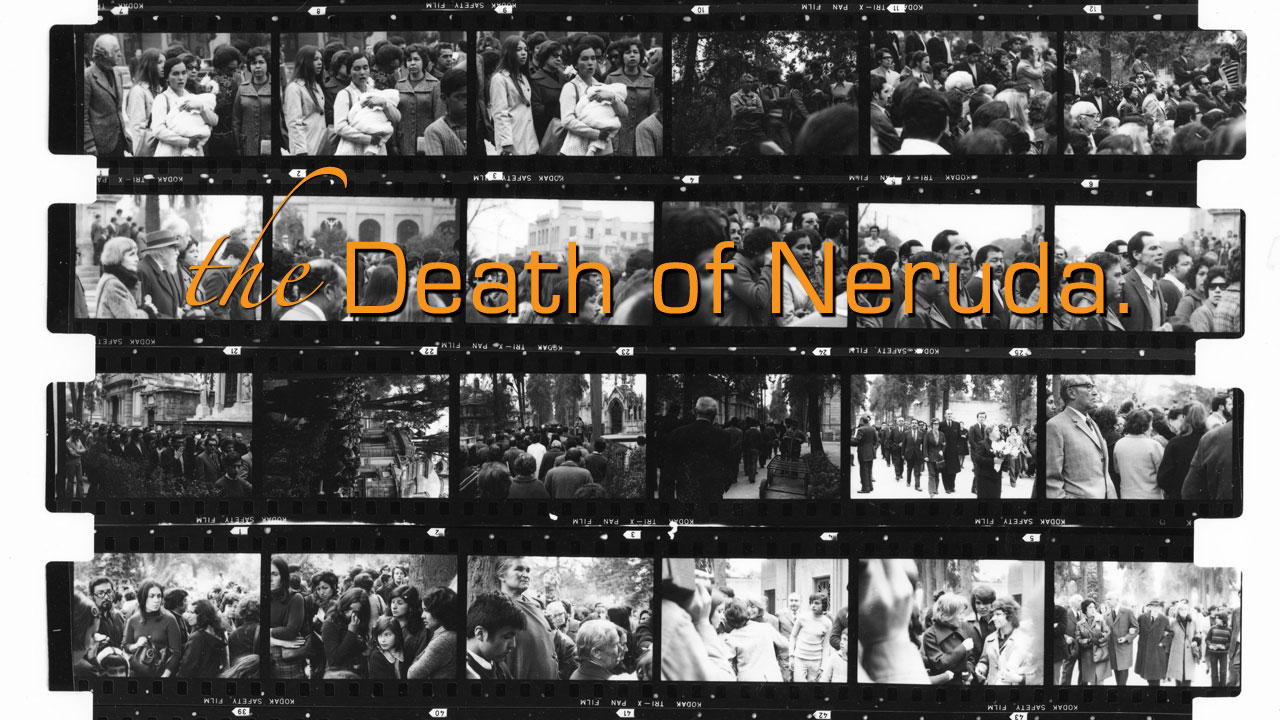

I was in Santiago de Chile 30 years ago this week, on 26 September 1973, the day Pablo Neruda was buried in the Cementerio General. In fact, I was only a few miles away when his body was lowered into the earth that he had so sensually celebrated. Looking back now, I could have so easily walked to that cemetery and joined the men and women chanting next to his coffin. Along with them, I would have chanted his name and, in this way, I would have said farewell. But I did not take that walk and I did not join their chant. In all honesty, I did not attend the funeral and the final journey of the poet who had taught me to love Chile and the Spanish language more than any other author in the world.

It is one of the few decisions in my life that I truly regret.

When I arrived in Chile in 1954 from the United States, a 12-year-old boy who had been born in Argentina and yet spoke barely a word of Spanish, I had not heard of Neruda and certainly could not have recited any of his verses. During the next decade, however, as I was seduced by Chile and its language, Neruda was to seep into my life and then, finally, to take it by storm.

My first encounter with the great poet, as far as I can recall, was at the age of 14. Lovelorn due to an impossibly luscious and distant girl a few years my elder, I was counselled by one of my classmates to whisper in her ear - if I could ever get close enough, that is -- the words: 'Puedo escribir los versos más tristes esta noche' ('Tonight, I can write the saddest lines'). My friend insisted that by doing so she would fall into my arms and surrender those forbidden lips. I timidly attempted to do this, but my delivery and accent must have been as deplorable as my timing. 'Neruda!' she retorted. 'That's from Veinte Poemas de Amor. You're the fifth kid to repeat those lines to me this month.'

BEFORE DISMISSING me completely, she left me with an epitaph for my aspirations: 'Why don't you try "Una Canción Desesperada"?' she said, referring to 'A Song of Despair', a Neruda poem I should have known. Obviously, many other youngsters in Chile were using and abusing the same tactic -- and if I wanted to impress the ladies, it seemed I would have to dig deeper into Neruda's repertoire. Soon enough, I was diligently immersed in the ardent couplets of Los Versos del Capitan.

In the years that followed, Neruda was to be my guide at every step on my faltering road to self-expression and re-invention. Vast and inexhaustible, he was always there, on the tip of my tongue, ready to interpret the hostile, mysterious world. Neruda was there for the plucking and the telling, an endless source for every mood and every requirement.

In fact, as time went on, he became indispensable. When I needed to seize the world in all its turmoil, explore my fears of dissolution or my hopes for a daily resurrection, and explore the fluctuating borders between dream and nightmare, there was Residencia en la Tierra. When it was a matter of naming the América del Sur I had now embraced as my own, there was the Canto General with its birds and rivers, its mountains and stones, all commemorated in their splendour and complexity. In the lyric 'Sube a nacer conmigo, hermano' ('Rise up and be born again with me, my brother'), the whole furious history of Latin America was retold with outrage for the forgotten and violated lives of the poor and dispossessed, with reverence for their dignity and labour.

And when it was a matter of looking at my own feet, of finding words for what it meant to bathe in the icy volcanic sea that Neruda also loved, or of discovering the enigmas of the artichoke and the condor and the colour blue, it was Neruda in his Odas Elementales.

Invariably, it was this poet more than any other who opened the exact colloquial window into the vocabulary of the heart, like a furtive best friend murmuring to me of a world full of wonders, asking all the while why the world could not be as beautiful for its inhabitants as it was for its poets. His was a world of politics, love, fish soup, alleyways, clocks, heroes, brothels, dictators, nuns, breasts, albatrosses, shoes, hands, carpenters. In other words, no matter what you wanted to know about life, Neruda had already been there. He had a surfeit and an excess of words, and most of them -- not every one of them, but most -- were pretty close to perfection.

And now he was dead and I was not attending his funeral.

He had died of cancer but also of sadness -- the sorrow of the coup against democracy on 11 September 1973, the heartbreak of the death of Salvador Allende and of so many other friends and compatriots being rounded up, tortured and executed. All of it was too much for Neruda who had spent most of his life fighting, as a communist, for the social justice and economic sovereignty that were being crushed by the military. A climate of fear had descended and now pervaded his native country, intimidating and silencing every citizen. It was of the sort that Neruda himself had often described in his poems. Tragically, the bloodshed he had denounced in republican Spain in 1936 and invited the whole world to see was now flowing in the streets.

Undoubtedly, it was this climate of fear that prevented me from attending Neruda's burial. I had gone into hiding after the coup and was looking for a way to leave the country. At the time, the most foolish thing I could have done -- I told myself -- was to make an appearance at his funeral. It was sure to be crawling with soldiers, the police and government spies.

Thousands of other Chileans, perhaps more desperate than I -- and assuredly more valiant -- decided otherwise. Defying the authorities, from all over Santiago they converged on the Cementerio General on that September day 30 years ago. Friends of mine later told me that it was at first a mute and desolate multitude, until a voice was heard from the back of the crowd, calling out: 'Compañero Pablo Neruda!' and hundreds of voices thundered back: 'Presente!'

Hearing this, the nearby troops were dumbstruck. They had no idea how to react to this homage to Chile's greatest poet, Latin America's most popular writer, and one of the most extraordinary voices of the twentieth century or, indeed, any other century. But then, before they could do anything, the same baritone voice shouted out: 'Compañero Salvador Allende!', asking us to recognize the dead President who had been buried anonymously only two weeks before. Again the mourners answered: 'Presente!' It was the cry of people who would have too much to mourn over the next 17 years of the Pinochet dictatorship.

NERUDA MUST have smiled at us from the other side of the grave. For he believed, above all, in the body -- its juices, its bones, its genitalia, its hairs and nostrils and skin. It must have been a vindication of his vision to realize that his supposedly dead body had become the spark and starting point for the Chilean resistance. Furthermore, his funeral gathering turned out to be the first attempt by his people to take back the public spaces now forbidden to them. It was symbolic that this inaugural challenge to the forces of doom and authority from on high surged from the farewell ceremony to a great poet, a man who had always proclaimed that poets were not gods but more like bakers or builders, entangled in the everyday life of ordinary men and women and sharing their fate.

It was fitting that it should have been those men and women who spoke out at his funeral, Chileans who had, like me, been nurtured and nourished all through their lives by the verses of Pablo Neruda. It was right that they should be the first ones to tell the world that their bard had not really left them, and to swear that they would keep him alive by remembering his words when they made love and drank red wine and breathed in the dazzling light of the sea. They would recall him when they were saddened at twilight and exalted at dawn.

Looking back, I believe Neruda would have wanted his last act on this earth to have been a prelude or maybe an intimation of something better, imagining a remote day when the planet would be worthy of the poems he offered us so generously. These poems still resonate and endure beyond his death and ours and -- who knows? -- might even endure beyond the death of our universe itself.